Vehicles and Firefighting Equipment

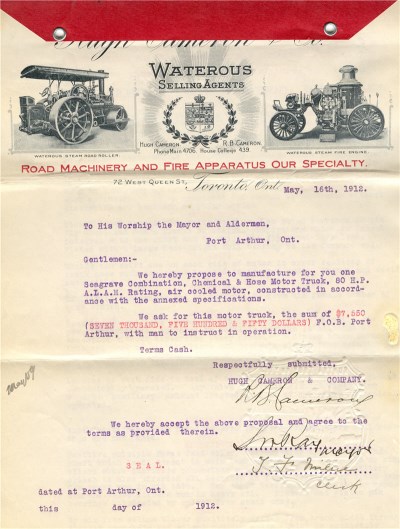

A variety of types of firefighting equipment has been used by the Fort William and Port Arthur Fire Departments. Over the years, this has included various hoses, chemical hoses, hand chemicals, hand pumps, foamite tanks, and fire hydrants. Hoses appeared to constantly need replacing: requests were put in nearly every year for additional hose.

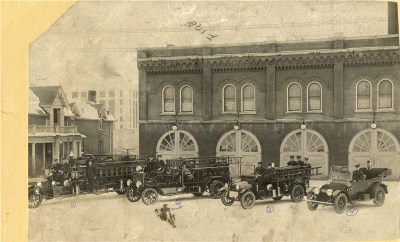

In Fort William, equipment was frequently moved around between the stations, depending on the age of the equipment and  needs of the station. For instance, in 1945, an outdated 1911 Trailer Ladder Truck from the Brown Street Station was moved to Central Station for use there, as a new truck had been purchased for the Brown Street Station. Of course, the older vehicle needed replacing the following year, as there were safety and wear-and-tear issues due to the age of the vehicle. Fire chiefs urged that vehicles and equipment should be replaced regularly, as the use of outdated equipment reflected poorly on a booming city like Fort William. There was a particular need for new equipment and vehicle replacements in the mid-to late 60s. Typically, the Department tried to disperse major purchases of equipment over the years in order to balance the need for modern equipment with realistic budget requests.

needs of the station. For instance, in 1945, an outdated 1911 Trailer Ladder Truck from the Brown Street Station was moved to Central Station for use there, as a new truck had been purchased for the Brown Street Station. Of course, the older vehicle needed replacing the following year, as there were safety and wear-and-tear issues due to the age of the vehicle. Fire chiefs urged that vehicles and equipment should be replaced regularly, as the use of outdated equipment reflected poorly on a booming city like Fort William. There was a particular need for new equipment and vehicle replacements in the mid-to late 60s. Typically, the Department tried to disperse major purchases of equipment over the years in order to balance the need for modern equipment with realistic budget requests.

The picture above was published by the Joint Fire Prevention Publicity Committee Inc. in the early 1960s, this poster shows fire fighting over the years. It begins with the “Bucket Brigades” and the technologies of the early 1800s, and moves towards the modern era. Some equipment is displayed, such as the hose reels, the steam fire engine, and the Fire Chief’s “speaking trumpet”, which was later replaced by radio technology. The bottom left corner depicts a pumper truck, one of the basic necessities of any Fire Department.

By 1961, Port Arthur and Fort William each had two pumper trucks. Port Arthur’s pumper trucks were capable of pumping 625 gallons of water per minute and 500 gallons per minute. Fort William’s pumper trucks were capable of pumping 625 gallons of water per minute and 600 gallons per minute. Five years later, Fort William made a request for a new fire pumper, which would  be a Mercury Truck Model M-700 from Port Arthur’s Consolidated Motors, at a cost of nearly $5,000 (it would be “reconditioned”, not brand new).

be a Mercury Truck Model M-700 from Port Arthur’s Consolidated Motors, at a cost of nearly $5,000 (it would be “reconditioned”, not brand new).

By 1961, the Fort William Fire Department had in its inventory two pumpers, two hose trucks, one aerial truck, a portable pump, one ladder truck, a salvage and rescue vehicle, and the Chief’s car. The Central Station also maintained a civil defense truck, to which a snow plow was attached in 1967 so that the truck could be used for clearing snow at Fort William’s three fire stations.

This was comparable to the Port Arthur Fire Department’s equipment during the same time period. In 1961, the department was equipped with two pumpers, a hose truck, a portable pump, a rescue truck, a ladder truck, an aerial truck, and the Chief’s car. The Department later purchased an auxiliary truck and an ambulance in 1966. When the Chief's car was replaced in 1960, the Department had bought a station wagon, that could also in an emergency serve as an ambulance.

Fort William’s Fire Department was able to apply for a new pumper  through the Emergency Measures Organization (EMO) in 1967, a programme through which the provincial and federal governments would subsidize firefighting equipment. According to the arrangement, the federal government would pay 30% of costs and the Province 15%, and the City would make up the remaining 55%. In 1967, however, available government contributions only totalled $1,500 (about 8%) of the $18,500 purchase, as about 40 municipalities had requested funding at the same time, and there was only $40,000 total available in the program. EMO subsidies were split across many different Fire Departments across the province, and the federal government's contribution was also threatened as they withdrew from the EMO program. The Fire Department, however, knew that the vehicle was desperately needed, and so proceeded with the purchase anyway.

through the Emergency Measures Organization (EMO) in 1967, a programme through which the provincial and federal governments would subsidize firefighting equipment. According to the arrangement, the federal government would pay 30% of costs and the Province 15%, and the City would make up the remaining 55%. In 1967, however, available government contributions only totalled $1,500 (about 8%) of the $18,500 purchase, as about 40 municipalities had requested funding at the same time, and there was only $40,000 total available in the program. EMO subsidies were split across many different Fire Departments across the province, and the federal government's contribution was also threatened as they withdrew from the EMO program. The Fire Department, however, knew that the vehicle was desperately needed, and so proceeded with the purchase anyway.

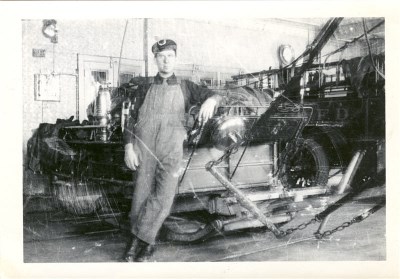

The proper upkeep of vehicles and equipment was of great importance. The condition of equipment and vehicles was always monitored in Fire Department Annual Reports, and the City would fund any necessary replacements. Vehicles had to pass an annual test to ensure safety and efficiency. Testing and maintenance was the job of the Department mechanic.

The importance of upkeep and modern equipment was made painfully clear in 1932, when a ladder truck from Fort William’s Central Station was unable to make it to a fire at St. Paul’s church, where ladders were desperately needed. The situation was relieved only when firefighters and other vehicles were recruited to  move the truck from the station to the fire. Not only was the needed truck delayed, but other firefighters and equipment were wasted on moving it rather than simply working to put out the fire.

move the truck from the station to the fire. Not only was the needed truck delayed, but other firefighters and equipment were wasted on moving it rather than simply working to put out the fire.

The Port Arthur Fire Department was often urged to expand its resources when it came to equipment. Given the size of Port Arthur, there were significant concerns about not having enough equipment on hand in the event of multiple or large fires. It was suggested, in accordance with the Canadian Underwriter’s Association and the National Fire Protection Association, that the Fire Department maintain six pumper trucks and two ladder trucks, with a crew of five or six firemen for each. Port Arthur had not been conforming to  these standards: they had only been maintaining three pumper trucks with three or four men, and one active aerial ladder truck with two men.

these standards: they had only been maintaining three pumper trucks with three or four men, and one active aerial ladder truck with two men.

In order for the Fire Department to house all the new equipment, a new, larger fire station would be necessary. This fire station would have to be in central Port Arthur, but also take into consideration the traffic flow and other local concerns. The proposed new location was in the west end, so the station would protect the areas west of High St. (in the Oliver Road area), and the west end areas of Brent Park and Shuniah Road (around Junot and River St.). The new station would relieve the other stations, especially Central station, of some of the territory they had been responsible for protecting. This hypothetical new station was anticipated for years, as seen in the Annual Reports of the Fire Department, but never materialized.

The two Fire Departments had managed, over the years, to acquire some impressive equipment. In 1948, the Port Arthur Fire Department purchased a 100-foot aerial ladder, which was publicly tested by reaching to the top windows of the Public Utilities Commission building, and to the top of the Prince Arthur Hotel. In fact, the Port Arthur Fire Department, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, was believed to be one of the top Fire Departments in Ontario in terms of equipment.

Although fire equipment and vehicles were vital, new purchases could sometimes not be made because of extenuating circumstances. For instance, during the Second World War, a decision was made not to purchase any expensive new equipment. Any extra costs would deprive the war effort of resources. This concern was echoed by a Fire Prevention Week advertisement in the newspaper that warned “Fire Losses Aid the Enemy!” (October 7, 1944).

Although fire equipment and vehicles were vital, new purchases could sometimes not be made because of extenuating circumstances. For instance, during the Second World War, a decision was made not to purchase any expensive new equipment. Any extra costs would deprive the war effort of resources. This concern was echoed by a Fire Prevention Week advertisement in the newspaper that warned “Fire Losses Aid the Enemy!” (October 7, 1944).

Radio and Communications

In 1952, the Fort William Fire Department acquired a new radio phone system, to make communications during alarms and emergencies more efficient. Shortly after it was installed, the Fire Department was able to help after the Pool 4A Elevator Explosion and be called back to fight two other fires simultaneously.

In Port Arthur, a request was made the same year for a new two-way radio system, and this was installed in Central Station the following year. Requirements for the system included being able to connect to the ambulance radio system, and to the Fort William Fire Department system. Being able to synchronize responses to alarms, and redirect calls, was worth the extra cost. In 1965, a phone message recording system was added, to prevent confusion and loss if a wrong address was pursued.

Street fire alarm boxes had been available to the public and used in the earlier days of the Fire Departments, so that members of the public could warn of a fire. By 1960, the last fire alarm box was taken down in Port Arthur, and Fort William expressed interest in revoking their street alarm boxes--with good reason. The use of these alarms was considered outdated (due to modern telephone equipment and other alarm technology), and they were frequently the source of false alarms. The alarm boxes were dismantled in Fort William the following year.

Protective Equipment

Of course, firefighting equipment also includes the protective gear that firefighters are required to wear. The City of Fort William provided formal uniforms to the firemen, which consisted of a coat, a vest, and matching pants and firefighting equipment consisting of a helmet, woolen mittens, shirts, fatigue pants, duty pants, rubber boots, and winter and summer caps.

The Port Arthur firemen were provided with similar gear. They had two uniforms: a formal uniform and one designed for actual firefighting. Clothing included peacoats, tunics, vests, trousers, shirts, and neckties for formal attire and overalls, rubber boots, and waterproof coats for fighting fires. The uniforms varied in style depending on whether the wearer was an officer or a fireman.

Requests for uniform tenders were placed in the newspaper. Potential vendors were required to submit a sample of fabric, information as to whether the garments would be made locally, and the price at which the item could be purchased. Among the regular clothing providers were Eatons and the local McNulty’s Ltd.

In 1952, a request was made for the Fort William Department to purchase gas masks, as there had been three incidences that year where firefighters were unable to enter buildings due to poor ventilation and an abundance of smoke. In Port Arthur, in 1955, improved air masks were received as well as a Stephenson Resuscitator to improve life-saving capabilities and the ability to fight fires.

For more information on this subject, or any other subject of interest, please visit or contact the City of Thunder Bay Archives.

Contact Us